Obstructive Sleep Apnea analysis and detection.

The project is to classify between normal people and patients suffering from OSA (Obstructive Sleep Apnea) with data-driven solution. An overnight sleep study in the sleep center or lab is required to diagnose OSA, and the result has to be scored manually. This procedure is expensive and inconvenient. Instead of wearing multiple sensors during the sleep test, the number of required sensors is reduced to one. The goal is to use only a pulse oximetry (SpO2) to process the collected data and help prescreen patients with OSA. First, Chris, Victor and me reproduced an OSA-prescreening system based on previous research results, using Chazal’s methodology [3] to repeat the experiements. The we built a two-stage machine learning model, modified from Chazal’s method, and made it suitably integrate into our bluetooth oximetry solution.

Introduction

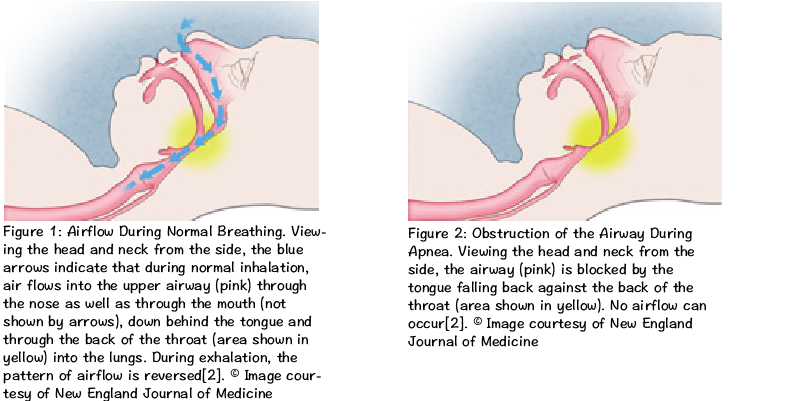

During the normal breathing process, air flows through the nose and/or mouth, past the back of the throat, and down into the lungs as shown in Fig.1. Instead, sleep apnea is commonly defined as the cessation of breathing during sleep, with a reported prevalence of 4% in adult men and 2% in adult women [4]. If breathing does not stop but the volume of air entering the lungs with each breath is significantly reduced, then the respiratory event is called a hypopnea. Clinicians usually divide sleep apnea into three major categories—obstructive, central, and mixed apnoea. Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is characterized by intermittent pauses in breathing during sleep caused by the obstruction of the upper airway as shown in Fig.2. When sufficient air doesn’t get into a person’s lungs, the level of oxygen in the blood falls and the level of carbon dioxide rises. After a few minutes of not breathing, a person may die. Fortunately, with OSA, after a period of not breathing, the brain wakes up, and breathing resumes. This period of time can range from a few seconds to over a minute. When breathing resumes, the size of the airway remains reduced in size. The tissues surrounding this narrow airway vibrate—what we call snoring. In other words, snoring is a sign of an obstructed airway, but it does mean that a person is breathing; silence might indicate that the airway is completely blocked [2]. In addition to snoring, the other symptoms of OSA are excessive and inappropriate daytime sleepiness, insomnia, problems with memory and/or concentration, fatigue etc. They may increase the risk of hypertension [5], cardiovascular mortality [6], and traffic accidents [7][8].

The severity of obstructive sleep apnea is indicated by the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) and oxygen desaturation levels [10]. The AHI is the number of apneas or hypopneas recorded during the study per hour of sleep. It is generally expressed as the number of events per hour. Based on the AHI, the severity of OSA is classified as follows:

- None/Minimal: AHI < 5 per hour

- Mild: AHI ≥ 5, but < 15 per hour

- Moderate: AHI ≥ 15, but < 30 per hour

- Severe: AHI ≥ 30 per hour

The oxygen desaturation levels, which are the reductions in blood oxygen levels (desaturation), are recorded during polysomnography or limited channel monitoring. At sea level, a normal blood oxygen level (saturation) is usually 96-97%. Although there are no generally accepted classifications for severity of oxygen desaturation, reductions to not less than 90% usually are considered mild. Dips into the 80-89% range can be considered moderate, and those below 80% are severe [10].

OSA is a frequently ignored condition affecting millions of people worldwide. Its common signs include loud snoring, restless sleep, and daytime sleepiness. Some serious symptoms are insomnia, depression, and even cardiovascular problems. An overnight sleep study in the sleep center or lab is required to diagnose OSA, and the result has to be scored manually. This procedure is expensive and inconvenient. Instead of wearing multiple sensors during the sleep test, the number of required sensors is reduced to one. The goal is to use only a pulse oximetry (SpO2) to process the collected data and help prescreen patients with OSA.

The polysomnography is a traditional method for assessment of sleep-related breathing disorders with the recording of electro-encephalography (EEG), electro-oculography (EOG), electromyography (EMG), electrocardiography(ECG), oronasal airflow, respiratory effort and oxygen saturation (SpO2) [9]. This make the sleep studies expensive for patients, because they require overnight evaluation in sleep laboratories, with dedicated systems and attending personnel. Hence, techniques which provide a reliable diagnosis of sleep apnea with fewer and simpler measurements and without the need for a specialized sleep laboratory may be of benefit. In 2000 PhysioNet and Computers in Cardiology conducted a challenge [11][12], “detecting and quantifying apnea based on the ECG”, to determine the efficacy of ECG-based methods for apnea detection. Besides there are several researches predicting the AHI by oxygen desaturation levels [13][14]. Therefore, in this project, we reproduce an OSA-prescreening system based on previous research results by using ECG and SpO2 measurements to detect the sleep apnea patients at different AHI levels.

Method

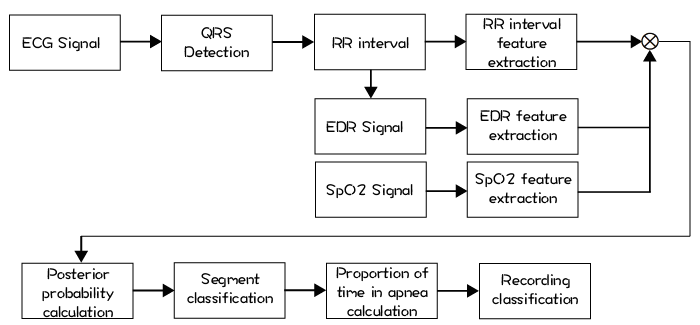

Chazal’s method is to build an automated system for detection of OSA as shown in Fig.3 [3]. The system provides two outputs. The first output is a time segment sequence (eg. 30sec-by-30sec, 1min-by-1min etc.) of classifications of “normal” or “apnea.” The second output provides an overall summary of the presence of clinically significant apnea and it is derived on the basis of the annotation sequence.

We slightly modified Chazal’s method. We also have two stages. Since we have label data for each epoch (30 seconds) sliced from the whole sleeping data, telling us how many times an apnea happened in an epoch. We can also resample an epoch into an time interval (longer than an epoch e.g. 1 mins). Therefore, the first stage is to train a regression model to predict how many times an apnea happend in an time interval. The output of the first stage then becomes a new feature in next stage. The second stage is to train a binary classifier with features, including statistical features extracted from the data of each person and output from first stage, to distinguish from someone has OSA and someone doesn’t.

Results

By averaging from Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Adaboost classifiers, the accuracy of our second stage is above 99% if we use both ECG and SpO2 signals. This is consistency to the result of PhysioNet 2000 Challenge [3]. The top 3 accuracy in Physionet 2000 Challenge are 100% in 30 cases, while we have more than 2000 cases. If we use SpO2 signal only, the accuracy drop to the range in 90%~95%. The variation of accuracy is due to the two apnea criteria rules of annotation: oxygen desaturation or arousal [15]. Even though the result of using only SpO2 is not as good as using both signals, with a small trade-off on accuracy, the whole prescreening procedure can be implemented with only a SpO2 bluetooth oximeter connected to a smart phone. It reduces the hassle of sleep test and improves the user experience.

References

- T.Penzel et al., Systematic comparison of different algorithms for apnoea detection based on electrocardiogram recordings, Med. Biol. Eng. Comput., 2002, 40, 402–407

- http://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/sleep-apnea/what-is-osa/what-happens

- Chazal et al., Automated processing of the single-lead electrocardiogram for the detection of obstructive sleep apnoea, IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 2003, 50(6):686-96. DOI: 10.1109/TBME.2003.812203

- YOUNG, T., PALTA, M., DEMPSEY, J., SKATRUD, J., WEBER, S., and BADR, S. (1993): The occurence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults, New Engl. J. Med., 328, pp. 1230–1235

- Durán-Cantolla J, Aizpuru F, Montserrat JM, et al; Spanish Sleep and Breathing Group. Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c5991. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ bmj.c5991.

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or with- out treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 2005;365:1046-53.

- Terán-Santos J, Jiménez-Gómez A, Cordero-Guevara J. The association between sleep apnea and the risk of traf c accidents. Cooperative Group Burgos-Santander. N Engl J Med 1999;340:847-51.

- MasaJF,RubioM,FindleyLJ.Habituallysleepydrivershaveahighfre- quency of automobile crashes associated with respiratory disorders dur- ing sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1407-12.

- AMERICAN ACADEMY OF SLEEP MEDICINE TASK FORCE. (1999): ‘Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research’, Sleep, 22, pp. 667–689

- http://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/sleep-apnea/diagnosing-osa/understanding-results

- T. Penzel, “The apnea-ECG database,” in Computers in Cardi- ology. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE Press, 2000, vol. 27, pp. 255–258.

- G. B. Moody, R. G. Mark, A. L. Goldberger, and T. Penzel, “Stimulating rapid research advances via focused competition: The computers in car- diology challenge 2000,” in Computers in Cardiology. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE Press, 2000, vol. 27, pp. 207–210.

- Magalang UJ, Dmochowski J, Veeramachaneni S, et al. Prediction of the apnea-hypopnea index from overnight pulse oximetry. Chest 2003;124:1694-701.

- Chung F, Liao P, Elsaid H, Islam S, Shapiro CM, Sun Y. Oxygen desaturation index from nocturnal oximetry: a sensitive and specific tool to detect sleep-disordered breathing in surgical patients. Anesth Analg 2012;114:993-1000.

- Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events—deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:597–619.