Redirecting people with complex conditions to effective care.

This summer in DSSG, we’ve been working on a data-driven criminal justice project with Johnson County, Kansas, part of the White House Data-Driven Justice Initiative. We pivoted from a vague and difficult scope, identifying the super-utilizers, to a more concrete and solvable problem, redirecting people with complex conditions to effective care. It’s more important to note that there are more ethical and operational issues beyond machine learning algorithms and models and those are the crucial parts of real-world data science; otherwise, it’s gonna be just a paper that won’t make any change at all.

Introduction

More than half of the people incarcerated in the United States report symptoms of mental illness, but jails and prisons are often poorly equipped to treat mental illness. To help these individuals, jurisdictions need to identify them before they enter jails or prisons and connect them to mental health services.

Data

Johnson County, Kansas provided data about individuals’ interactions with three county systems: the criminal justice system, emergency medical services, and county mental health services.

Criminal Justice Data: Inmate characteristics, jail bookings, bail, charges, pretrial services, court cases, sentencing, probation.

Emergency Medical Services Data: Patient characteristics, medical impression, transportation, triage, call time and location.

Mental Health Data: Patient characteristics, diagnoses, treatment modalities, service dates, programs enrolled, discharges.

By linking individuals across these datasets, we can see how people move between the systems they represent. The Venn diagram below illustrates the proportion of Johnson County’s 575,000 residents who have touched each system in the last 6 years. This is the venn diagram of the three datasets. In light blue is the population we focus on: Those with histories in the mental health and criminal justice systems.

Method

We applied machine learning methods to predict which individuals in our population of interest (people who have interacted with both the mental health and criminal justice systems) are most at risk of entering jail in the next year.

Matching/Linkage

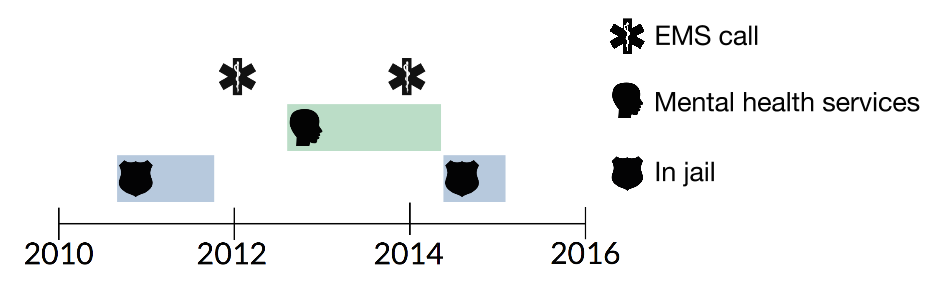

The data provided by our partners come from three different data warehouses. We linked records across them, allowing us to compile timelines for individuals’ interactions with all three, such as the one below.

Feature Generation

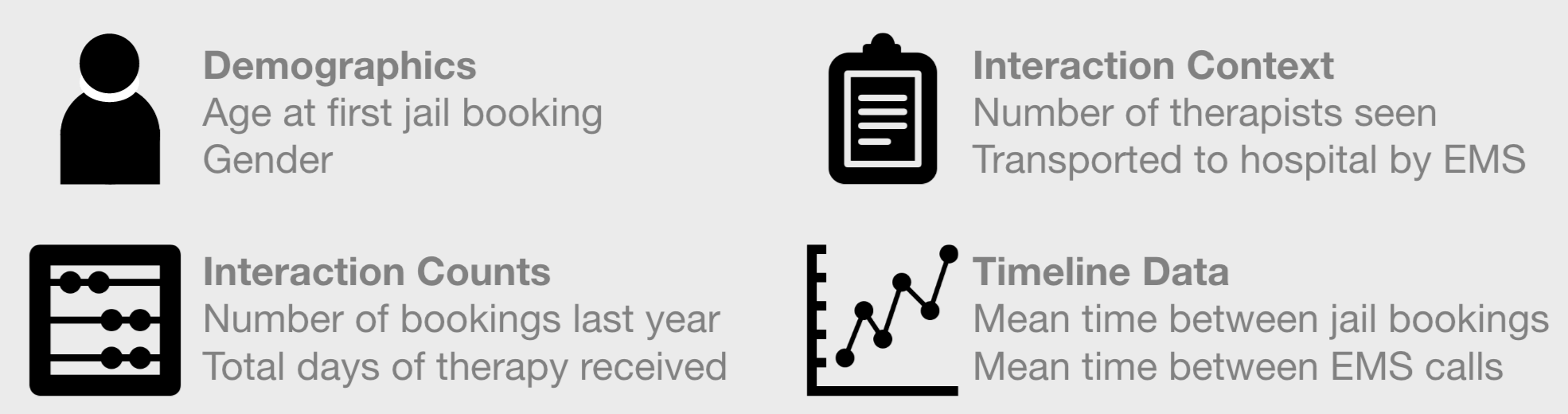

From these records, we generated individual-level features to predict future jail bookings.

Data-Driven Modeling

We reserved data from 2015 for testing and then trained suites of models (e.g., decision tree, random forests, logistic regression, and gradient boosting) for each year prior to 2015 beginning in 2010.

Model Validation

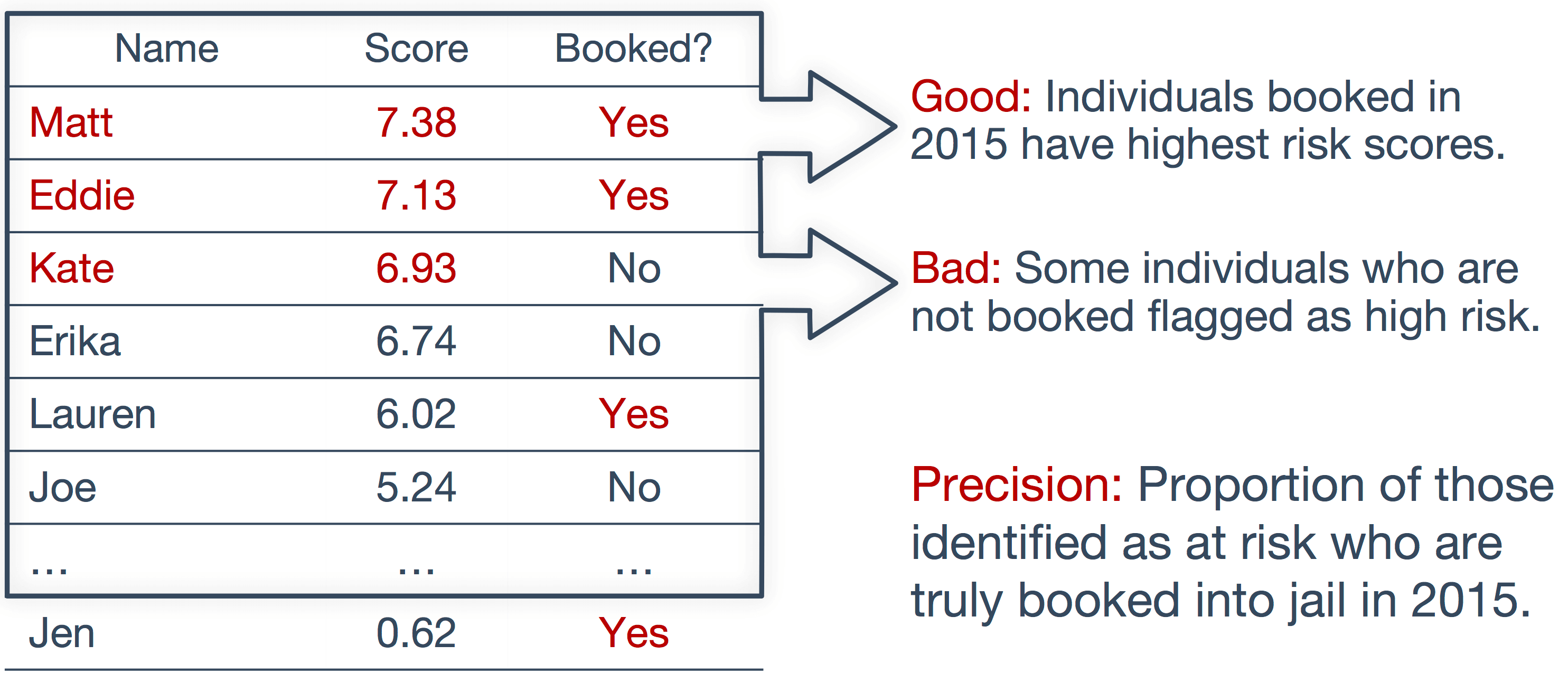

We generated risk scores for every individual as of Jan 1, 2015 and classified the top 200 individuals as at risk of being booked into jail. We evaluated the model based on the precision of these predictions.

Result

Our best performing model was a random forest model that has a precision of 0.52 at the top 200 predictions. In other words, just over half of individuals we flag as at risk are booked into jail in 2015. In contrast only about one person in ten of our population of interest are booked into jail that year, meaning our model gives a five-fold prediction improvement over this baseline.

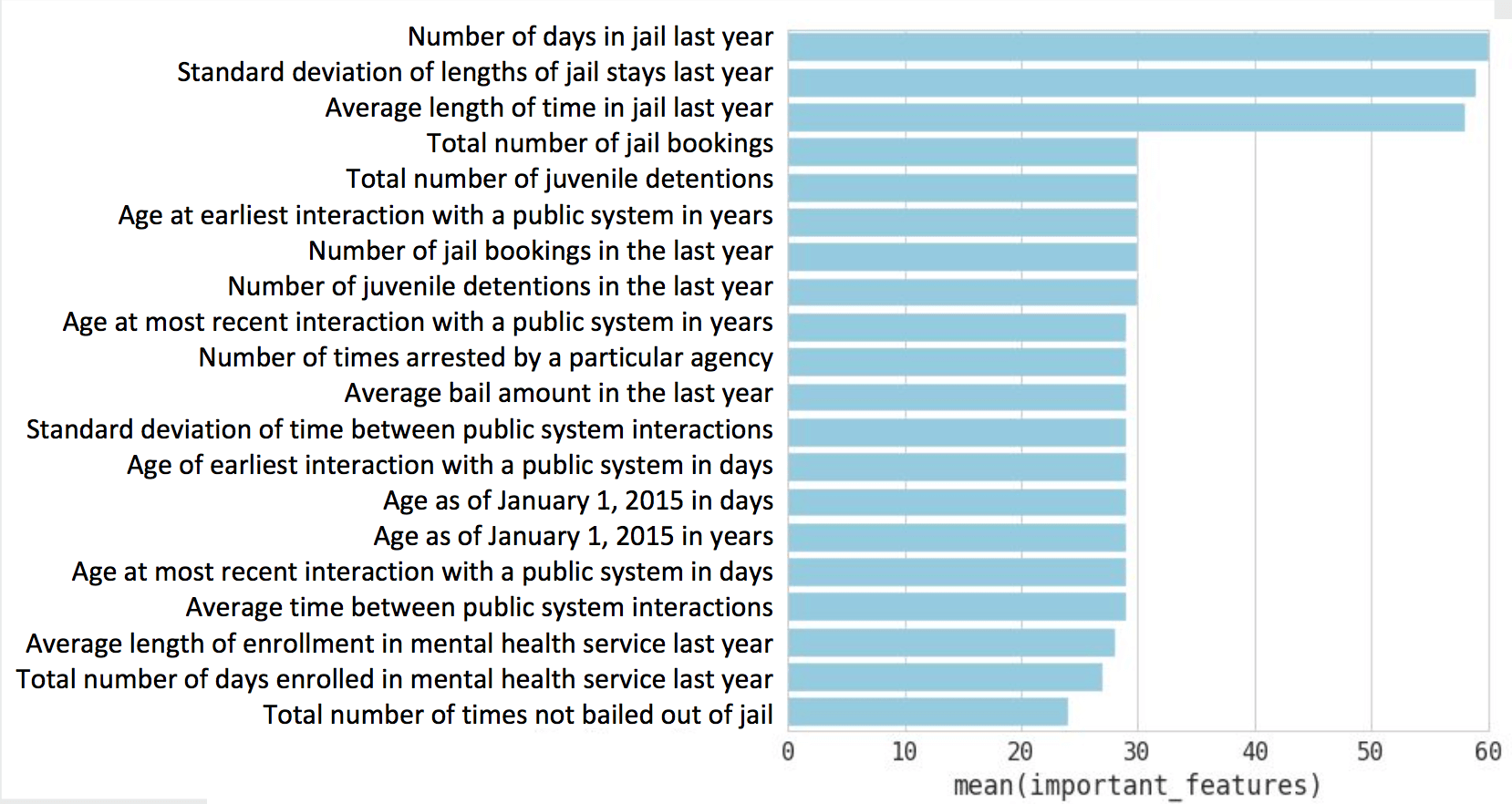

Our model also tells us which features are most important for predicting jail bookings in this population, shown below.

Impact

Johnson County employs four mental health caseworkers who are embedded in police departments as co-responders. Part of their work is following up with people experiencing mental illness who have made contact with the police. If they were to prioritize outreach to the 200 individuals we identified as at risk in 2015, every other contact would reach someone who was booked into jail that year. On average, each person on our list who was booked spent 2 months in jail—at a cost of over a quarter million dollars to Johnson County. Moreover, at the time of their booking, these individuals had been out of contact with mental health services for an average of over two years.

This presents a substantial opportunity for Johnson County to design interventions that would reconnect those at risk of re-entering jail with mental health services that may improve their lives and prevent contact with the criminal justice system.